During pitches, I have to give a short blurb about my background. This is the story I wish I could tell.

Like many kids, I learned how to code through video games. On February 11th, 2005, I sat in our kitchen while my parents cooked dinner. My dad was watching a show called The Screen Savers on a small CRT TV, the kind that tickled your fingers if you touched the screen after turning it off. That day, they talked about a game called Blockland.

A big Lego fan myself, I jumped to install this game and immediately got addicted. I fell in love with the infinite creativity of a building sandbox and the ability to talk with complete strangers who were all excited by building. We'd spend hours making jokes with each other, building skyscrapers, and coming up with puzzles. The same way Lego captivates my imagination, Blockland did so without burning a hole in my parent's wallet. Blockland predated Minecraft by about six years, but I think many kids fall in love with Minecraft for the same reasons.

Blockland also had a community forum: a place where people would post their creations and talk about life, but most importantly for me, talk about how to modify the game. You see, when people love something, they want to make it better. I wanted to make Blockland better.

One day I discovered a guide to modifying the game.

The first beginnings were simple. Windows Notepad, manual indentation. Hours of syntax errors, asking my dad what a variable was. Boundless frustration, but all worth it for that dopamine rush when it actually works and the new Lego bow I had imagined was working on the screen in front of me. And more importantly, because it was a game, I could share with everyone else who loved it.

Turns out, seven years later those mods still stood the test of time, long after the era of CRT TVs.

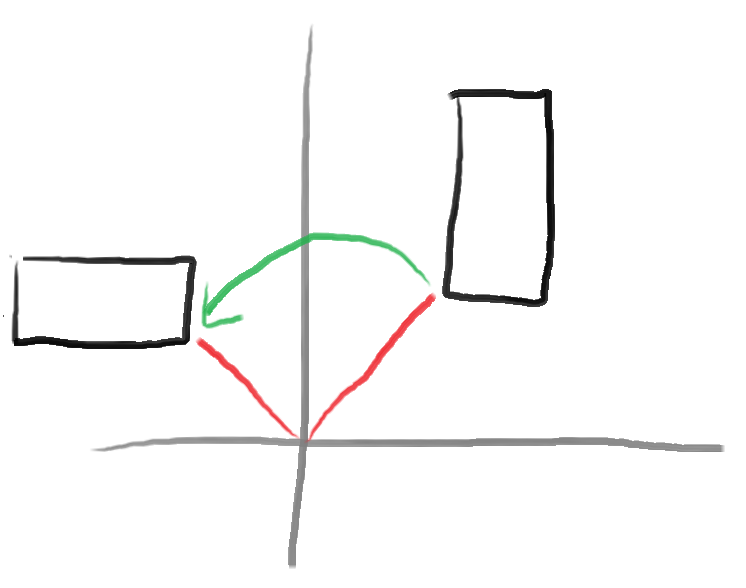

My favorite mod that I wrote was called Custom Shifting. Blockland operated in a discretized three-dimensional world, but the Torque Game Engine it was built on was a fully-featured 3D engine. Some modders realized this and added a feature that allowed setting the exact orientation of a block. I took this mod one step further and allowed players to scale, transform, and rotate with their keyboard, effectively turning Blockland into a rudimentary 3D modeling program.

This mod was also the best geometry lesson I had ever gotten. I actually asked my geometry teacher how to do rotations about an arbitrary point via matrix multiplication in rectangular coordinates. He told me that I should convert everything to polar, do the transformation, then convert it back to rectangular. I don't remember much else from that class (sorry Mr Stuckey) but I definitely remember that conversation. Turns out I had invented something similar to features in real 3D modeling programs like Blender.

I wish I had the foresight to screenshot the insanely creative structures people made. Everything from racecars to roller coasters, statues to skyscrapers. People began twisting and turning blocks, shaping and molding them to fit their imaginations. I remember after releasing the mod, suddenly the bar for creativity skyrocketed as everyone had millimeter-grained control over their Lego bricks' positions.

I'm still proud of the code I wrote because it was my first taste of seeing how I could impact a community with just an idea. Video games taught me that I could create anything I wanted to with the right logic.

Blockland's community was small though. It wasn't until Neopets, Runescape, and Maplestory that I'd realize how much games influenced larger communities. The botting communities behind these games were huge! Hundreds of thousands of kids coming together to figure out how to automate their games to gain an advantage. Auto-chat spammers, auto-clickers, boss battle winners, you name it. And the platforms kept trying to detect us too. It was sort of an arms race between kids who barely knew what HTML was and actual, established engineers.

I'd hack together some AutoHotKey scripts with some basic image detection and let them run overnight or while I was at school. I'd actually publish some of these bots and others would constantly try to improve them with more fervor than any GitHub pull request I've seen. It was really like trying to build software without having ever learned how to code, but crazily it worked! Whatever crazy ideas I had to save myself from having to manually level up were just a few lines of code away.

Web games were also where I managed to start my first actual business. From these scripts, I grew to about $500k in annualized revenue at the peak. Sometimes I miss the simpler days of hacking scripts together and shipping them out. I never wrote tests: I didn't even know what they were. I just implemented whatever idea landed in front of me.

Web games taught me that I had the ability to influence a lot of people with the right choices. My code didn't even have to be good, it just had to be useful.

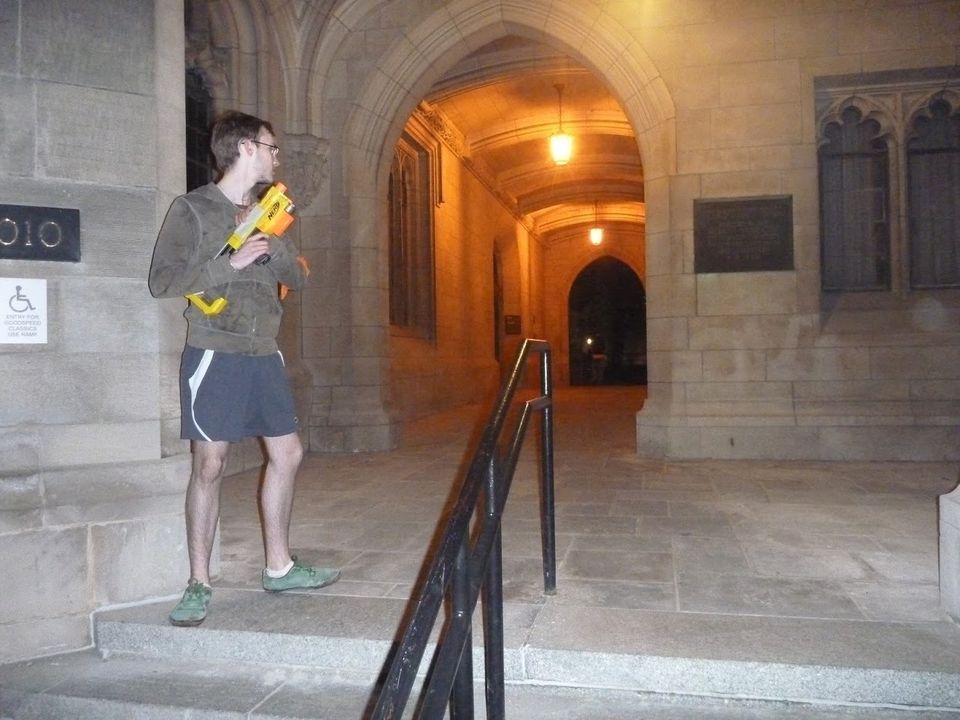

When I moved to college, I started to outgrow the online games I played. But gaming always stuck with me. I quickly became the creator of UChicago's Humans vs Zombies game, an alternate reality game played on campus. You can find a more detailed account of the game's history and structure over at this post, but not that much differently from video and web games, I really had no idea how to run the game and just dove right in.

Our team made it work, however. We strove to focus on individual players and try to make the experience amazing for everyone. Over the course of my tenure running the game, we grew the game from zero to 400 players, which was about 10% of the undergraduate population at the time. Some of our events had way better turnout than I could've ever imagined when I matriculated, with hundreds of students running across the quad chasing each other in a chaotic version of tag. It was exciting to see that I was just trying to have some fun and in the process, I found others having fun with me.

But what struck me the most was the impact that HvZ had on some of the players. Some players said that HvZ was how they found friends. Others said that HvZ helped them get through depression. We had built a game that got even the most anti-social UChicagoans to have a bit of social life. The key was in figuring out how to structure the game so they could build the social life that they wanted, not the frat parties imposed on them by society.

I hope you read this and other stories of HvZ players and understand that it has helped a lot of people be happy in a school that struggles with depression. --anonymous player

Alternate reality games taught me that focusing on game design and incentives instead of just telling people what to do can catalyze some truly magical moments in the community. I'm really proud of HvZ and to this day strive to have the same impact on people that I did in college.

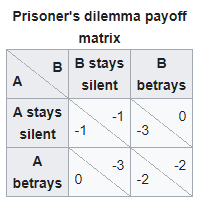

Besides HvZ, while at UChicago one of my favorite classes was introductory game theory. From Prisoner's dilemma to Bayesian games, the idea that interactions between players could be modeled and analyzed was astounding. Suddenly, so many of the interactions I saw, emergent behaviors and choices that people made, could be justified from the simple framework of a game.

It was also right about the time when I was at UChicago that Dr Richard Thaler's nudge theory started to gain traction. To me, this theory was revolutionary. All the economics I had learned before suggested that the best way to influence behavior was through direct incentives: taxes and subsidies. But here, behavioral economics was saying that another way to influence behavior was through small structural changes.

Nudge theory gave credibility our theory for why HvZ worked so well. It wasn't just that the game was entertaining: that in itself wouldn't have made people socialize. Humans vs Zombies helped people socialize because it changed their underlying perception of the world just slightly. It nudged them towards cooperating with others to make it to their next class alive. It gave them a subtle cues via a colorful bandana to help people find others who also cared about avoiding zombies. It enabled conversation topics around heroic rescues and daring escapes.

if you want to get somebody to do something, make it easy --Dr Richard Thaler

Formal game theory showed me that the impact I had with games wasn't a fluke or luck, it was actually something structural and could be studied. It showed me that with a bit of study and care about the structures of the games, then games like Humans vs Zombies can be designed, engineered, and improved. That the unfortunate Nash equilibria could be mitigated by nudging prior beliefs.

These days, I spend my time on Huddle. I'm captivated by the idea that technology can connect people and I believe that video is a medium that far outclasses any other text-based or image-based forum we've seen. Video has a way of humanizing and connecting people in a way that is only rivaled by meeting them in person. The only reason I think video can offer something unique compared to an in-person meeting comes down to a nudge: it's easier to hop on video.

So then the question comes down to: how can we build a video platform that emulates meeting people as close as possible? I don't want to build a platform that offers artificial connections or tries to be the only place to connect, I want video to simply nudge people in the right direction to enable them to build those connections on their own.

I spend a lot of my time thinking about my experiences with both playing and building games. I see the potential of platforms like Twitch to catalyze the same feelings of connection that I saw with HvZ. I think the right approach to a successful platform will involve a bit of game theory and a bit of luck to keep incentives aligned. Otherwise, we're just shooting in the dark and hoping to be successful.

Szélesy says he grew up feeling isolated, largely spending time in front of the glow of a computer. "[I streamed to] escape loneliness and depression," he said. While he has mostly been streaming without an audience, every so often an errant person will drop by and stick around. Even if this person never comes back — and they often don’t — the small spark is enough to keep Szélesy going. --The Verge

Hopefully, I'll find that building these social games works. I'd love to see game theory take a more prominent role in our decision making and I'm out to prove that it works. With the tech industry grappling with AI and its ramifications, I believe the right answer towards a better world is just a small, engineered nudge away.

Games have always played a special role in my life. They've captivated my imagination, influenced how I see the world, and formalized the changes I want to make. The ways that games can bring people together, both directly and indirectly, remains an area that I wish were better understood.

And despite thinking more about structuring games, I still play games. As of writing, I've been playing Valorant, loving the sports-like strategy and communication involved with a team.

After all these years, I've discovered my love for studying incentives and probabilistic game theory and finding new ways to build games to foster community and connection. I haven't found a formalism yet for why games work so well, but there's always time for another act. Wanna play?

Comment on this post on Twitter